An

Ecosystem of Writing Ideas

by Jack Collom

by Jack Collom

For ten years I've taught a graduate writing course called "Eco-Lit" (Ecology Literature) at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. Eco-Lit is offered by Naropa's Writing & Poetics Department, but welcomes students in other departments and local citizens at large.

In Eco-Lit I strive to be expansive, to suggest far more than we can thoroughly cover. We use a 400-page coursebook as well as many supplements (especially now that nature writing is gathering steam and becoming more than isolated "cries in the wilderness"). Such a hefty load may confuse students at first, but eventually makes sense to them - sometimes long past the end of the course. We read and discuss (as literature, as representations of nature) poems and essays by recognized luminaries of the field, the writings of Thoreau and after - John Muir, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, Leslie Marmon Silko, Gary Snyder, Edward Abbey, Barry Lopez, Gretel Ehrlich, Susan Griffin, Loren Eiseley, Annie Dillard, Robinson Jeffers, et al. We also go back in time - to Boethius, Thomas Nashe, Gilbert White - and around the world - to Issa, Coyote and Jataka Tales, Orpingalik the Eskimo songmaker, //kabbo the Bushman, and others. Beyond these "nature people," we read fine poets of all subjects in the belief that a good poem, in being intensely relational within itself, is an ecosystem whatever it's nominally about. Writers of scope inevitably include - are included in - nature. We seek that sense, too, in comic strips, diaries, songs, lists, letters, slang, politics, slogans, definitions, fables, rebuses, jokes, and science jargon. And we touch on perhaps the greatest nature book, Moby-Dick.

Looking at a wide variety of forms allows us to keep up with, even help to lead, the profound and rapid changes going on in humanity's knowledge of and attitudes toward nature. In my view, the word nature is peculiarly misunderstood by most of us. It's seen as something pretty one might sniff in passing, or as something disastrous such as a flood - in any case, as something secondary to the world and culture of Homo sapiens. It's something, in fact, that we're busy replacing with pavement, hydroponics, genetic engineering, zoos, animation, tree farms, and virtual waterways. It's something too dumb for irony.

In truth, nature is everything. It gains breadth from its subsidiary, limited meanings: beauty, wildness, source-of-life, and all their specifics. It gains poignancy through its contradictions. It's the big matrix; we're a few dots not only in it but of it. The "of" is what we forget. "Of" is identity of processes. Recognizing "of" is the springboard of love, without which there's only destruction, of ourselves and others. Jackson Pollock's remark, "I am nature," still has the ring of an outrageous cry - although it's just an overdue recognition. The word ecology means literally "knowledge of the house." In the sense that our house is now the entire world, the study of ecology has come to be a comprehensive study of the relational - the spreading interdependence of all things.

I encourage my Eco-Lit students to bring in their own favorite writers, variant viewpoints, and new facts. I continually hear about new, dynamic writing ideas from them. The more the merrier; I'd rather we struggle with bewilderment than oversimplify the possible links between writing and nature. In addition to our varied classwork, we go on a couple of fieldtrips each semester. These can simply be nature walks with writing, in the mountains or plains. Typically and inevitably, however, they take place in settings that include people-generated stuff; in this and other ways we learn that no separation between nature and humanity is possible. At the end of the semester we assemble a class anthology, for which each student contributes a certain number of pages. Many (but not all) of the included pieces reflect the class assignments. What follows is a sampling from those anthologies (keep in mind that these are writing students, mostly new to "nature writing"). It's also a walk through the many forms of writing I have my students experiment with.

* * *

The prime act that must precede writing - or talking - about nature is observation. Since pure perception cannot remain unaltered by language and our human psychology, the class discusses this question of phenomenology and we write with it in mind. We strive to approach, with our very limited senses, a fairly accurate take on a "leaf of grass."

Direct Observation Poem

mind

between

me

and

mountain

--Jeff Grimes

Rhubarb red like a starched erect sinew sticking out of

the dirt: the Stem

Ending in triangular formations sharp drooping like

floppy garrisons: the leaves

Margarine yellow starting to melt on a skillet pan

intricate like doily patterns: the Head

One tarnished copper green leaf the tip of it starting to

change into rhubarb red like rusting plate mail

The most important part of a wrinkled dried-out sun-scorched

leaf like a wet walnut brown sock left twisted upon

itself after being wrung out

This burnt potatochip leaf is barely connected to the

stem

--Aaron Hoge

Another basic of nature writing is the sense of place. I urge students to write about place in any or all of several ways: by cataloguing what's there; by focusing on one or more of the senses; by narrating themselves into the pictures; by writing acrostic poems about the place; or by making a small portion of a place stand for the whole (synecdoche). Poet and writer Merrill Gilfillan put it this way:

Look closely. Make notes on all the particulars you can in-place - sketch shapes, colors, sounds, aromas - and when you think you've done that, give it five minutes more; the summoning and staking of details leads, of course, to details-in-configuration, in context, i.e., to relations, root of all esthetics (and ethics). The same goes for a barrier reef or a freightyard or Gary, Indiana.

Ultimately, the poet finds his or her own way to depict the here and there:

a place called here (excerpt)

The days are stacked against what we think they are.

--Jim Harrison

stacked against what we know we are while wet flakes flower on the hoods of red volvos and drape aspen branches like lace. We know we were in love but the snow came too late. flouncing in on the tail of red robes layered against dusk. at the mercy of turnings, squinting to catch a stack of metered time rolling off slope of moon or the bridge of a nose that reminds you who you were. your own sweating breasts against a killing dream¾

the earth stacked in favor a bird's wings, ladder or plates grunting their way from hell to blue. In streams of water whistles like air, dispersed falling, who we think we are. fallen¾

--Shanley Rhodes

Enviropoem

I am in my

body wrapped in skin

skin clothed in cotton

in a room with florescent light

and a slightly stuffy air

in a building with classrooms

offices and library books

on a patch of ground with other buildings

making a school

surrounded by streets

stoplights and cards

in the middle of Boulder

full of random or purposeful human activity

dependent on electricity and gas

connected by telephones and computers

under the mountains

where goldseekers from the east

thought it looked like a good place to winter

one hundred thirty-one years ago

and never left

end of plains beginning of mountains

end of Arapahoe when the Americans came

only the statue of Niwot left

squatting by the creek west of 9th St.

staring at downtown Boulder

with its restaurants and banks

the creek by which he sits

comes down a canyon

drops 3000 feet in fifteen miles

is fed by other creeks

going back to lakes and glacier

if you keep walking up

you can see a good deal of it all at once

to the east, Boulder, Denver, brown cloud

pollution now makes its own horizon

a dingy line in the sky

and there are always airplanes

flying over all of it

and there are always satellites

orbiting above them

always a moon

always a sun

they always return

and the earth

so far

remains

--Chuck Pirtle

The journal is an I-remember of the present: it always encourages us to notice our surroundings and our five or six senses. Here's one that displays a rocky compaction:

Grand Teton (excerpts)

August 1st

0300 - Dark and cold. Wind blowing from the west. Very little sleep. Shared the cave at 10,500 feet with pikas. Up, already dressed. Headlamp on. Find Wesley and Bob. Quick breakfast - oatmeal and coffee. No one talking. Grunts.

0415 - Start down through boulders and talus. Wesley leading. Down about 1000 feet then up to the Lower Saddle. Headlamps catch pikas. Occasional bird noises¾.

0600 - On the saddle between the Middle and Grand Teton - glow to the east. Pre-dawn. Still cold. North through long boulderfield. Smells of human shit. Exum Guides must still be dragging pack-trains of tourists up the ridge. Purchase an experience. No one around. Breathing hard. Look west into Idaho. Almost light now. To the east Signal Mountain, Jackson Lake, the Snake River, Alpine Lakes¾.

0915 - On the summit - very small place. Only other people there two crazy Brits-one chain-smoking. Sun beginning to warm, but not much. Take a few pictures. Look north to Cascade Canyon and all around. Still very clear.

--Bill Campbell

The Portrait, or Sketch, is also one of our staples. It's a natural with animals. As always, details rather than generalizations make the reality:

The Magpie

Mulling and clucking under its breath

like the tanned and stained

homeless man downtown.

Huge and black and white

gloriously white, like rabbits' fur.

Breast feathers pristine

without benefit of a rasping,

rough cat tongue.

It mewed and whispered,

rolled its small obsidian eyes,

tail flashing blue pearls upon liftoff.

The branch vibrating

seconds after

the last huff of a wingbeat

pushed the air away.

--Deborah Crooks

Inspired by Charles Simic's poem "Stone," in which the poet whisks our imaginations inside a plain rock and finds magic there, "Going-Inside" poems aim for the active empathy with "the other" so basic to an ecological sense:

Tripping in Cell

Stuck in sticky cell jam

my hands clasp the walls and

Martha Graham did a dance like this

using an elastic bag as

elastic plasma membrane containing

slurpy elastic blob blopping cytosol.

I bounce against altochondria

climb twisted DNA into a Jungian mansion

up is down into

ancient rooms

can't breathe for the dust

I'm no ape! no¾

a whale¾

am I a whale or an ape or a

whale of an ape!

amoeba pear viking¾.can't decipher this

genetic code caught between a chicken and its egg.

Whatever¾..I'm stuck in this lethargic liquid

bang my head on a nucleus

feels like I've got a rock in my shoe.

--Karin Rathert

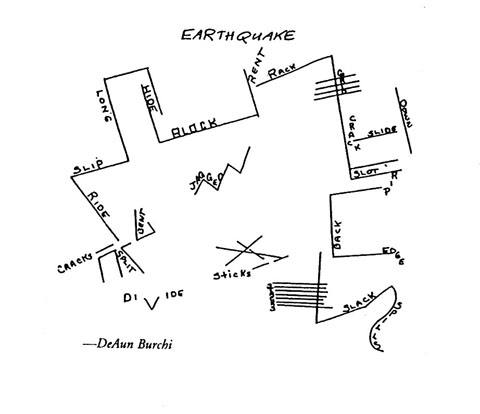

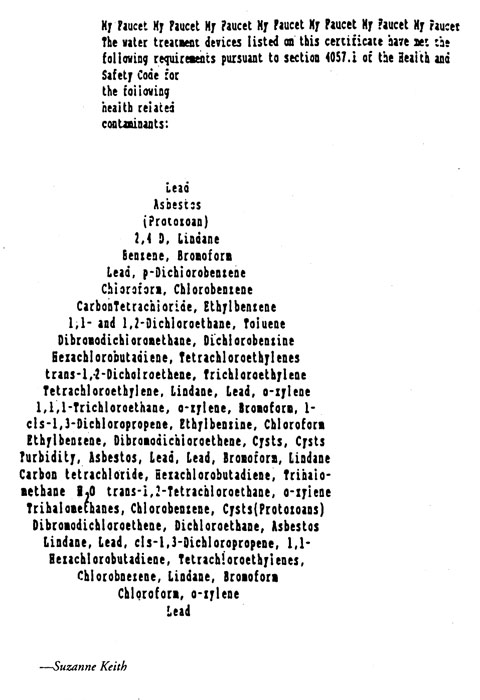

Concrete poetry emphasizes the visual (sometimes sound) aspects of letters and words: Writing has always had a pictorial component (we can still see it in present-day Chinese), just as language has always had a musical component. In the Middle Ages, poems were constructed in the shapes of crosses or angel's wings, and so forth. Here are two contemporary works from my Eco-Lit classes:

I encourage experimental approaches (following Mother Nature's lead). My Eco-Lit students have often, I think, invented new forms, or at least new formal modes:

With Their Voices They Are Calling You

Whales ivory walrus

coral phylum coelenterata cult

scleractinia gorgonia

brain star fire

nematocyst

black fin fan tube sponge basket porifera

seals black sea cream

tea leaves in teal stream

millions of minnows in silver

negligees

royal ribbon morays

anemone

lemon lilac lily

emerald sapphire jade

interleafing coral cables in diamond lattice

angels in striped pajamas

French butterfly queens

rosequartz candy in yellow cellophane wrapper

Tahiti starfish seaworms lions

cucumbers elephants

squirrel fish wild wedding veil

noble brandy gold

yolks -- sun and moon -- flounder globes

seams sugar sand

porpoise saxophones patterns around

noise shark tabernacles

inset -- vestibule for

snapper grouper jacks

pisaster star

little feather sister

sea urchins with pedicellariae

Caribbean buttercups

celestial kelp

duster worms

hermit crabs and scallops

Rays - round butterfly bat true

--Resa Register

"Silent Eyes"

---

Ghost Smile

"The words have no meaning,

but the song means,

Take it, I give it to you."

--Navajo

Soft

Footsteps

Light

Howl

Coyohohohohehehe

heyaheyaOhohohoh

eheheyaheyaOhoho

hheheDANCEheyahe

yaohohohohhehehe

heheyaheyaOhohTE

On

Dirt

Earthen

Ground

Deep

River

Dry

Tears

CROhohohohhehehe

heyaheyaOhohohoh

heheheSOAKyaheya

Ohohohohheheheya

heyaOhohohohhehe

heyaheyaOhohohoW

In

Dirt

Earthen

Ground

--Mike Lees

Loomings

The sky

is the color of

split

cantaloupe

and it is

raining

seeds big

as Santa Fe

boxcars on

the heaven

of the human

tongue.

--Randy Klutts

Yet another basic of nature writing is the question mode. Nothing else stirs information about or turns it over like a question:

Is Nature Moral? (excerpt)

How can I think well enough to answer that question when the beauty of the sunlight on the pine needles keeps catching me? When there are blue jays eating berries from the vine on the side of my house? When some new magpies just moved in to the tree next door? When I'm kept up at night by the shuffling and scuffling and growling and chattering and lip-smacking of all ages of raccoons outside my bedroom window? When the singing of coyotes awakens me at three? When the stars are so bright I linger for too long beneath them? When there's a pulling in my chest at the way the wind and sun are making everything look at this moment?

--Sarah Brennan

Wallace Stevens's great poem "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird" gives us the perfect form for looking into multiple truths:

seven ways of looking at a cloud

1 i, a disappointed child

when told that clouds weren't solid

2 clouds gathering into massive anvil fist

muttering over the silent desert

splitting rain onto cracked red ground

3 the rain-giving clouds are distinctive

with their countless pouchy buttocks

mooning the earth below

4 Lenny the lenticular was a

mean machine, leaning out across the sky

a speeding ellipse against the blue

5 cumulette puffs of white dropped like wads of cookie dough

their cloudbottoms dark and flat against an unseen nonstick pan

6 a cloud is the ultimate philanthropist

poor in his youth, he becomes generous

with age and girth

sharing his water-horde at last

7 in ancient days a man was turned into a cloud

forever banned from the earth

but at night his form loosened into mist

and he touched the face of his love as she slumbered

--Chris Burk

One of the most colorful formats is the recipe. Recipes show how elements can be combined to create new elements. They have a distinct vocabulary that is familiar to everyone. Recipe poems encourage wild imaginative leaps - but no food allowed!

Boulder Valley Surprise

boil igneous rock for millions of years

let stand until cool

when inland seas subside

uplift red sandstone, crimp edges

grind soil with glaciers

decorate with trees, evergreen and deciduous

then add large mammals, fish and birds

transfer humans with stone weapons

across the Bering Strait

convert large mammals

to food clothing and shelter

now add other humans from the east

sprinkle liberally with iron and gunpowder

in a large well-wooded valley

sift for gold dust

construct wooden buildings, then add brick

steam railroads, a shot of whiskey

then, with a large spatula

smooth out even layers of concrete

on any possible surface

sauté in carbon monoxide

bake with electromagnetic waves until saturated

in a large sealed container

cook plutonium until doomsday

garnish with shopping malls, tanning salons

takeout chicken, video arcades and massage parlors

set blender on purée

bring to a boil

run from the kitchen

--John Wright

The acrostic poem has been practiced for thousands of years: basically, a word is set vertically, and lines of a poem "spill out" of the letters. Acrostics serve any topic with great structural readiness, since the "spine word" resonates through the poem. Here's one with the whole alphabet, for that inclusive effect:

All together now, longer lives are special, longer lives are

Better. Because one gets to learn a lot,

Cuz one has the opportunity to learn from mistakes,

Dumb mistakes, dumb stupid mistakes like

Environmental disasters, like

Flooding lowlands for recreation, like

Giant dams that hold back water, like

Habitat destroyed in name of progress, like

Incan ruins unearthed and shattered, like

Jays being shot because they're too loud.

Kill, kill, why not kill? this globe this planet this

Land that bustles on its own much noisier than the

Moon. Oh, opal light, eclipse and mountain -

Now is the time to strike back, reform the earth,

Our knowledge unleashed for centuries without

Prior thought, without consideration of the side effects, without

Questioning the start of what once begun will take lifetimes to

Reverse. There is a

Sweet trickle of clear water, there is a tiny stream

Trapped beneath the underbrush, singing beneath the

Unborn ferns, where all the fiddleheads pop up like

Violins and accompany the stream.

Where has it all gone and why are these places now named "treasures"

eXactly where a small valley was, not far from where

Yellow poppies battle with winds, their skinny stems the strings of

Zithers still playing for us, still playing for us, can you hear them?

--Sten Rudstrom

"Everybody has a water story," exulted poet Sheryl Noethe. Here is an example of the form from Eco-Lit:

Water Autobiography

3 A.M. Longs Peak Trailhead: I strap two liters of water to my pack.

2 P.M. Fredericksted: Hot, very hot. I roll off the raft and into the cooling Caribbean Sea, and bob like a cork

11 A.M. San Juan River, Utah: A wave catches me. I'm pulled under and am embraced by the current.

10 P.M. New York: We took long hot shower together, saving water in the 60s drought.

8 A.M. Lyons: A dead battery on cold winter morning I was late, late for school, late for work - the battery needed water.

4 P.M. Taj Mahal: Two naked children's bodies lie lifeless by the Ganges, their innocence swept away by the lapping holy waters.

11 P.M. Tip of Long Island: With our toes in the icy waters, we sent our spirits to Kohotec to become One with the Universe.

1 P.M. Hesperus: Very pregnant with my own, I break the water sack of a cria (baby llama) and help him emerge, feeling my own child move within me.

5 A.M. Hesperus: The warm soothing bathwater eases the labor pains as I wait for the midwife to arrive.

2 A.M. Lyons: "Maaaaaaaam ¾ Maaaaaaaam, I want some water."

5 P.M. Mediterranean: The sea is calm, eerily calm, not a ripple, just the slightest telling whisper from the north.

9 A.M. Top Longs Peak: The first liter of water was drunk on the way up - now with the second we toast our success.

6 A.M. Outside New Delhi: "Water is running." I slipped from my tent wrapped in a lungi with my towel, soap, and cup in hand to perform our morning ablutions with the women in the irrigation ditch.

8 P.M. Lyons: What it was specifically I don't remember, except perhaps that impish look, but we started to laugh and giggle, the three of us together laughing, laughing so hard that the tears rolled down our cheeks. We embraced with contagious giggles, my girls and I.

6 P.M. Bedminster: Old Tom and I sat on the river bank fishing and drinking beer and talking of life. He was 72 and I was 7 ½.

3 P.M. Fredericksted: It hadn't rained for weeks, the cisterns were empty. A crack of thunder the skies opened and we ran about dancing and shouting and tried to drink the sky.

7 A.M. Wherever: I splash the marvelously cold water on my face - Good Morning!

9 P.M. Far Hills: The rains just didn't stop, the water rose and rose, it was brown and muddy, it took the old cow, the footbridge, and the willow, then it stopped and slowly receded.

12 P.M. Kabul: The fact that he said it was the water gave me little consolation as I lay there bathed in sweat, folded in agony and praying for relief or death.

4 A.M. Mediterranean: The waves buffeted the Eostra about, the skipper yelled orders, the jib was in shreds: Poseidon had definitely lost his cool.

1 A.M. Amsterdam: The subtle movement of the houseboat lulled me into a deep sensuous sleep and dreams of Eros.

7 A.M. Blair's Lake: We scattered his ashes as he had wished - void of emotion.

10 A.M. High Time Farm: Dressed in a long white gown, my tiny bald head sprinkled with water, I received my name.

12 A.M. 12th Street: It was some movie, she said goodbye and I let go like a tropical storm, the tears flowing for every goodbye I ever said or that was said to me.

--Suki Dewey

As I noted earlier, this is only a sampling of the writing forms my Eco-Lit students try. We also do field notes, list poems, imitations, chant poems, definitions, haiku, haibun, lunes, letters, phrase-based acrostics, speeches, sonnets, plays, sestinas, and prose narratives. [You can find detailed descriptions of these in Poetry Everywhere (Teachers & Writers Collaborative), a book I wrote with Sheryl Noethe.]

We also experiment with different types of collaborations. Writing collaborations can be as myriad in form as writing itself. Collaboration by its essence (multiple causation) exemplifies the spirit that moves ecology. It's also a lot of fun, and can help escort a reluctant group into the joys of writing. And it helps free up student minds to a wider range of connections.

My students write essays throughout the course. Some are critical responses to readings. One is to research a local (Colorado-wide) eco-situation and write about it. The final paper is an essay on Eco-Lit - what's happened, what's happening, what will or should happen. One student, for example, traced ecology themes in music and song.

Some might argue that we should master one or two forms (styles, genres), but I believe that generally in creative writing, as in learning different languages, the more variety you undertake, the more mastery you achieve. When language exemplifies its subject, the impact is considerably strengthened and diversified. Obvious examples would be a poem about the sea having line-lengths that resemble waves or a poem about emotional upset moving zigzag on the page. When poetry discusses nature as if from a great height then nature seems both bounded and lowered. Sometimes, nature is only allowed to be a blank screen on which we project our emotions. But the realization that we are part of nature is growing. Our human culture - truly amazing though it is - may be less complex than the legs of a spider, or than our own cellular existence. What better way to use our indeed unprecedented cultural gifts than to build bridges back to our larger selves?

I think both older styles of nature writing and the currently accepted ones are fine; I have no desire to replace them, only to add to them. Language works as a field, a geometry, in which anything can take place, and the definition of nature should be something like "that within which we bob and swim." Were someone to argue that depth is more important than breadth, I'd say that depth consists of variation even more than breadth does.

* * *

I have also taught poetry to elementary, junior high, and high school students. For over twenty-five years, I have borrowed, stolen, been given, adapted, and made up well over sixty writing exercises for school children. All of them, I believe, are good for teaching nature writing. And, in their variety, they resemble an ecosystem. Here are a few of my favorite ones for the younger students (but not exclusively), with notes on how they physically relate to nature:

ANATOMY POEMS - personifications of body parts (the bones strike up a conversation with the heart, for example).

BUMPERSTICKERS - inventing these (e.g., REMEMBER WATER?) is fun and helps wean us from a sanctimonious reverence for nature.

"CAPTURED TALK" (students pull language from all around them: signs, books, overheard chat, TV, etc.) - a gleaning, like berry-picking; the rhythm and comedy of language tend to stand out in such collections.

CHANT POEMS - emphasis on rhythm and repetition, both of which operate abundantly in nature.

COLLAGE - grafting, hybridization.

COLLABORATIVE POEMS - exemplify the mulitiple truths and relational emphases that energize all of nature.

COMPOST-BASED POEMS (after Walt Whitman's "This Compost") - rot, and how life is fed by it.

CONCRETE POETRY - language forming aural or visual patterns, even recapitulating natural shapes.

CREATIVE REWRITES - personifications (or other adaptations) derived from science texts, resulting in such creations as talking winds or volcanoes.

"HOW-I-WRITE" PIECES - process-oriented, breaking habits down into physical details, bringing out the connections between writing and the most homely particulars in your life.

"I REMEMBERS" - list poems composed of lines each beginning "I remember¾" can release hundreds of intricate memories, making nature immediate.

LIST POEMS - an expansive way to talk about anything.

METAPHORS - I see exercises in metaphor as objective correlatives of the relational.

NO-WARMUP DELIVERIES - not only spontaneous but unguided, as sudden events in nature seem.

ON POETRY - "a slow of flash of light that comes to you piece by piece" (by a sixth grader).

ORIGINS (after Jacques Prévert's poems, "Pages from a Notebook") - playful little reverse creation myths ("The music teacher turns back to music," wrote one first grader).

OUTDOORS POEMS - being outdoors and writing a circle or path of observations.

PANTOUMS (Southeast Asian form with a weave of repeated lines) - like the cycles of nature.

PICTURE-INSPIRED WRITINGS - for example, one student wrote from a closeup of a cabbage leaf, describing it as a faraway galaxy.

POLITICAL POEMS - compassionate noise.

PROCESS POEMS - letting language be subject to mathematical processes, as nature is.

QUESTIONS WITHOUT ANSWERS - "Where do all the noises go?" The poem is a response (but not closure) to the question posed.

SPANISH/ENGLISH POEMS - students can write poems in which the two languages are mixed, as in a garden.

TALKING TO ANIMALS - "Tyger, tyger, burning bright" and other possible conversations.

THINGS TO DO IN¾ -- another way to project the mind outward (into the Brain of the Bumblebee, the Bottom of the Sea - or one's own kitchen).

USED-TO-BE-BUT-NOW¾POEMS - (I used to be¾, but now¾) playing with and against cause and effect.

WALL-OF-WORDS - distributed objects, announced words, and readings-aloud during writing time all help emphasize scene as source, so that nature writing not only discusses, but also models, nature's processes.

* * *

I've saved my favorite nature writing idea for last.

The first time I asked some of my elementary students to respond directly to the idea of Nature, using creative writing, was one Earth Day years ago. First I spoke of list poems: lists, or catalogues, have been a common element of both poetry and practical life for millennia. They are packed with information and encourage students to use surprise, to play with odd or wide-ranging juxtapositions. List poems tend to be rhythmic and full of energy.

I suggested that we make list poems from the idea "Things to Save." To give the word save the right context, I said a little about the looming ecological problems facing the world, but I didn't want to preach to the students. I also let the students know that they didn't have to feel restricted to "nature items" for their things to save; they should feel free to include personal things and favorite things - little sisters, books, or the teddy bear with a missing arm and its eye pulled out on a rusty spring. In this way, we could indicate that nature and civilization are interconnected.

The usual precautions about what helps make good poetry were appropriate at this point, so I told them that details are better than generalities. (Don't simply save "trees, animals, and water," save the lopsided old sycamore by Salt Creek where the grey-cheeked thrushes sing.) It takes imagination not only to create fantasies, but just to see what's in front of you, to go beyond a "bird' or a "bush." I also tried to show the students that it's both fun and necessary to create variety in their "things to save" writings, variety not only in the items listed but also in the kinds of items ("wild horses, acorns, smiles"). I asked them also to vary syntax in their pieces - not to get into the rut of "Save the blank / save the blink / save the blonk."

Here is a selection of these "Things to Save" pieces by younger students:

I'd like to save the sweet chocolaty chewy candy bars

that melt in your mouth, the warm cozy pillow that you

can't wait to sleep on, I'd like to save green meadows

that you run barefoot across running and running until

you collapse on the wet soft grass, the hot days when

you try to eat ice cream but it melts and plops on your

foot, I'd like to save the amusement parks where you go

on a twisty ride and throw up all over yourself but that's

just what you thought would happen, I'd like to save the

little green bug my big brother viciously killed six

months ago, I'd like to save the world all green and blue

and beautiful, I'd like to save the little things that

everyone enjoys.

--Juli Koski, fifth grade

clouds, white shadows in the sky, cotton candy white as the lining of

silk, soil black as coal, koala gray as rain clouds, trees tall as

the sky, polar bears white as ever, dolphins swimming in the sea.

--Jessica Flodine, fifth grade

The darkness of shadow-like wolves

darting across the night like

black bullets, and the moon

shimmering like a sphere of glowing mass.

Let us save lush grass, green as green

can be, but, best of all,

imagination glowing with joy aha,

images it is composed of, it is this

that is making the earth grow

with flavor and destination.

--Fletcher Williams, fifth grade

Poem #1

Save the Earth

Poem #2

Save the red fox, the white-tailed deer, the blue whale, the bald eagle, the black bear, the spotted owl, and animals not discovered yet¾

Save the black and white lily bug

Save the striped toad

Save the bunga-bird

Save the Galápagos hare

Save the green ten-legged spider

Save the rock troll

Save the hairy lizard

Save the Antarctic elephant

Save the Asian fire squirrel

Save the yellow-tailed monkey

Save the snow otter

Save the white-eyed dog

--Marco Barreo, junior high

I would like to save the colors on Earth

White as the snow

Blue as the sky

Night

Sunlight

Yellow as the sun, daffodil and bees

White as snow, whiteout and gems

Red as blood, flowers and your heart also hair

Orange as the fruit, gold earrings I see around

Green grass and shrubs

Darkness

The Black at night, in your eyes and in your hair

The Purple flowers and Purple polka-dot pencil you see

The Blue tears and Blue book covers

Gray we see in dreams.

--Shannon Foley, fifth grade

And finally - proving that this exercise can work at all levels - here is a poem by one of my Eco-Lit students:

Save the pearly everlasting dried broken at the roadside.

The sound of Arenal at night. Lava

and parakeets in flocks, and storms.

Save hills and high cliffs, save

animal teeth, save

fur and claws and tendons and bones.

Save stars but change the constellations if you want.

Save baobab trees,

llamas, rusty old meat grinders,

the organ grinder's monkey. Save

old shoes and hair.

Save caterpillars, nasturtiums,

grass-of-parnassus.

Save chokecherries

and phosphorescence,

sea horses, flies.

Save stone walls for walking,

and drift wood on beaches.

Save things that live in the Indian Ocean.

And things that swim in the South China Seas.

Save sand.

Save music and humming and whistling through teeth.

Save people on streets, but don't save the streets.

Then sumacs, and fescue and fenugreek seeds,

and ladybugs, aphids, paper-birch, leaves.

Touch-me-nots. Cockroaches.

Carnivores. Herbivores. Omnivores. Fields. Save

seed shadows. Leaf litter. And marshes. Save

duff.

Sea shrimp and squid ink and

octopus feet, and

hurricanes. And 80-knot winds. And

sailboats thrown onto high cliff roads.

And slugs and snails and scallops and scarabs.

Kestrels and nightshades. Vipers and honey.

Save blue things. Save bower birds.

Devil's club, mulch.

Save sea otters, ospreys and

things the color of stone.

--Saskia Wolsak

Reprinted from The Alphabet of the Trees: A Guide to Nature Writing, edited by Christian McEwan and Mark Statman, Teachers & Writers Collaborative, New York, 2000.

BROKEN NEWS || CRITIQUES & REVIEWS || CYBER BAG || CYB FI || EC CHAIR

FAREWELL, GREGORY: A POESY BURST FOR CORSO || FICCIONES || THE FOREIGN DESK

GALLERY || LETTERS || POESY || SERIALS || STAGE & SCREEN || ZOUNDS

©1999-2002 Exquisite Corpse - If you experience difficulties with this site, please contact the webmistress.